Lew's Writings

Ball Valve Mania

Plumbers frequently use valves of many different types to control the flow of liquid in pipes. Sugar makers are to great extent plumbers, and these valves are an indispensable part of their operation. They tend to sprout like mushrooms in modern sugarhouses, and their sheer numbers can be overwhelming. A quick look at our operation revealed 6 in the canning room, 9 in the evaporator room, 18 in the RO room, 28 in the sap sheds, and 85 in the woods. This doesn’t count the 10,000 check valve taps in our trees, or the ones I probably missed.

Common valves in sugarhouses include the shut-off kind (most common), or three-way (allowing you to direct the flow in two different directions), or check (allow movement in one direction only), or float (shuts off flow when the float rises to a preset level). Back in the day, shut-off valves were called gate valves, and worked by turning a circular handle a few revolutions to lower the “gate”, which arrested the flow. Then, someone designed the ball valve that stopped the flow with just a quick ninety-degree turn of the handle. You could even tell if it was open or closed by glancing at the angle of the handle. These were a big hit with sugar makers who live in a constant state of immediacy, and are always looking for labor saving devices. Their ease of use was a definite factor in their rapid propagation.

This abundance of ball valves, however, is not entirely a rosy picture. Turning just one of these valves the wrong way (which happens more frequently than your average sugar maker would care to admit) can have very undesirable consequences. The following are a few examples from my memories of thirty-seven years of fiddling with these gadgets. They are listed as cause (C) and effect (E).

C: Closing flow to the lower sap tanks, and due to distractions, forgetting to then open flow to the upper tanks.

E: This left the sap release pump with no outlet, and the elevated pumping pressure ruptured the release tank vent line, and countless gallons of sap sprayed all over the sap shed.

C: Setting the three-way valve next to the vacuum pump to the wrong water source. This large pump is water cooled, with either water from the house, or from the permeate tank when full. I forgot to switch this valve back to house water when the permeate tank had emptied.

E: Water in the vacuum pump cooling reservoir soared to over 150 degrees creating a very steamy pump room. When I entered, it looked like we were evaporating sap there also.

C: Forgetting to close the valve that allows concentrated sap to drain from its tank into the evaporator, before concentrating a new batch of sap.

E: Most of a whole batch of concentrated sap (its worth I am too embarrassed to acknowledge) overflowed the evaporator and spilled all over the sugarhouse floor. It took multiple washings to eliminate the sticky foot syndrome.

C: Opening the sap feed to the RO Machine (this machine concentrates the sap), but forgetting to close the permeate feed. Permeate is the pure water that the RO extracts from the sap. It is stored in a separate tank and runs back through the RO at the end of a concentrate cycle to clean its membranes.

Traffic control in the RO room

E: A concentrate tank full of “concentrate” that was much less sweet than the incoming sap.

This last snafu completely baffled me at first. The year was 1990, and I was concentrating sap with a newfangled RO for the second time. RO’s were just becoming popular in the sugaring world and this was the first I had ever owned. The first batch had gone smoothly and I was awestruck by the difference boiling concentrate rather than raw sap made. This second time I was adjusting the machine to concentrate to a higher level, and was keeping a close eye on the sweetness level of its output. The incoming raw sap sweetness was 2% sugar, and the machine was producing 8% concentrate, which was what I was hoping for. Checking it an hour later showed 6%. I was in a rush as usual, and distracted by other problems. That was a year of expansion for us, and I was working the bugs out of a lot of new equipment. I brushed this odd reading off as a faulty test. I finally checked the sweetness again several hours later, near the end of the concentration cycle, and to my horror it read less than 1%. I figured it must be a bad hydrometer. Even if the machine was not concentrating as efficiently as it should, there is absolutely no way its discharge could be at a lower sweetness than the incoming sap! Checking with a different hydrometer showed the same result. Impossible!! How could this possibly be?? Pressured by a strong sap run, I was very anxious to boil, but there was no way I was going to boil diluted sap. I battled with this riddle for over an hour until my straining gaze finally snagged on the open permeate valve. The sap tank was situated higher than the permeate and therefore had a stronger feed pressure when full. Thus, when I first began concentrating, the RO in-feed was mostly all sap, but as the sap tank emptied, it became mostly all permeate. Another day in the life of a frazzled sugar maker.

Cooling the Beast

We have a new 10 hp pump, which applies a vacuum to our maple sugarbush tubing resulting in a greatly increased sap yield. It is a very loud, masculine, belligerent beast with a hot disposition. It dominates the sap shed where it lives during sugar season and needs constant surveillance. Like a nuclear reactor it will overheat in a heartbeat if not continuously cooled with fresh water.

It is March 6, and after a rather slow start to sugar season it is time to fire up the beast. The sap is finally starting to run and there are so many other issues demanding my attention that it is imperative this task be performed quickly. It should be so simple; fill the 80-gallon reservoir that holds the cooling water and hit the switch. But wait, what is that puddle oozing around my feet? A closer flashlight inspection shows water pouring out through a cracked fitting where the drain ties into the tub.

My heart sinks, as this fitting (if I ever knew what it’s called I can’t remember) is not something you are likely to find at the local hardware store. Why didn’t this crack reveal itself at the end of last season when I would have had time to deal with it? To make matters worse, this particular fitting is an odd sized 1 ¼” and in a very restricted spot where a standard sized substitute wouldn’t fit anyway. Furthermore, it is a Sunday, which means closed supply stores. Unfortunately, sugar season could care less about Sunday being a day of rest. Trying to collect sap without vacuum when it is running like this could mean the loss of at least a thousand dollars over a 24-hour period. Running that hot-tempered beast without a coolant is not an option. It is at times like this when the immediacy of sugar season can be overwhelming.

I am not about to let a small drain hole ruin my day. This problem will be, must be fixed today with whatever I can get a hold of, even if it means sitting there using my hand as a plug. Searching hopefully for a less radical solution, Jake informs me he thinks the hardware store is open today with shortened hours. Calling them I ask sheepishly if they stock an I don’t know what its called fitting - as if I didn’t already know they wouldn’t have one. Two trips later, burdened down with an array of threaded fittings, pipe nuts, gasket material, and space-age sealant that seemed to cost almost as much as the new pump, I am ready to create my own fitting. Alas the standard thread length is too short to accept rubber gaskets on the thick walled tub. Getting desperate, I imagine contact cementing a rubber piece over the hole, but know that would be short-lived, so close to the vibrating beast. This stupid little 2” hole is really starting to get on my nerves, when bingo, I suddenly think of tapping the hole to accept a standard, in-stock male pipe fitting!

In the early afternoon, as I reassemble the pieces, the temperature quickly drops below freezing, which effectively shuts off the run and negates the satisfaction of my problem solving. The Lord seems intent on keeping sugar makers humble.

Lew Coty 3/6/11

Easter Sunrise Sap SURGE

It is Easter Sunday and the sun is rising, revealing a clear blue sky. It has been a cold night, but the higher elevations of Nebraska Knoll Sugarbush, especially the south facing slopes of Keystone, are already beginning to thaw under a strong, late March sun. The trees here are getting restless as the solar heat riles the sap in their veins. The lower slopes and Valley bottom however, are still under the grips of colder temperatures.

There are eight main lines entering the sap shed, arriving in four pairs of wet and dry lines, each coming from different sections of the bush. The wet lines transport the sap downhill from the trees, and the dry lines transport the vacuum to the trees. This morning the lower wet lines were still solidly frozen when the sap began running higher up. As pressure built from this blockage, the sap was pushed into the dry lines, which began running “wet”.

Chief of operations was monitoring this situation at the release tank where the lines end in the shed. I stood like a soldier preparing for battle, as I knew by the large volume of sap pouring out of the dry lines, that when the ice blockage melted out, an overpowering sap surge would follow. The wet lines soon began to trickle, and within minutes were running at full capacity. Outside, the torrent of sap was pummeling the lines where they curve at a right angle into the shed, making them vibrate. We call this phenomenon line thrash.

The two-horsepower pump, which pumps the sap from the release tank into the holding tanks, was quickly overwhelmed, and the vacuum was shut off. This pump, which is triggered by a float in the release tank and usually runs in cycles, was now running non-stop. It was pumping the sap into one of the twin 1200-gallon storage tanks in the shed, which are connected by a 1 ½” drain, and normally fill simultaneously. The tank was filling so quickly, that the sap level didn’t have time to equalize with its twin, and was soon about to overflow. There are two large 3200-gallon tanks in the upper sap shed, which are the backup when the lower tanks are full. I was averse to filling them at this moment since they were in bad need of cleaning (I had intended to clean them while the lower tanks were filling). Help arrived just in time to clean them before much sap was lost.

I quickly discovered the situation was still out of control, as pumping the sap uphill slowed the pump down just enough to prevent it from keeping up with the incoming deluge, overflowing the release tank. My solution at this point was to direct the sap into the lower tank, which by then had equalized enough with its twin to allow a little more in. Just before it overflowed, I changed over to the upper tank until the release tank was about to overflow, and then back to the lower. This cat and mouse game went on for the better part of an hour before the chaos stabilized. Amazingly, I lost very little precious sap in the process.

A sugarmaker would never admit there is such a thing as too strong a sap run, but experiences like this test that opinion.

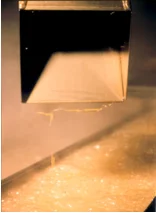

Three inch inlet to release tank overwhelmed by incoming sap.

Lew Coty March 31, 2013

Falls Brook Cabin 2/24/13

Falls Brook Cabin was erected in the summer of 1995, in large part, by the children of Nebraska Valley. For the preceding several years my ten-year old son Freedle had been enveloped in a pioneer paracosm. Among other frontier activities, he had been busily erecting wood forts, scattered near our home, with whatever poles he could find or cut down.

In the spring of that year he announced he was going to build a log cabin above Falls Brook, which runs through the center of our land and sugarbush. I didn’t think much of it until one afternoon when he returned with ax in hand, looking a little shaken, saying a tree had almost landed on his head. Examining the site, about a third of a mile from the house on top of a bank overlooking Falls Brook, was a nicely prepared ten-by-twelve foot cabin site nestled into our maple grove. Much to my alarm I also discovered a nearby, severely leaning tree. It was about a foot in diameter, axed mostly through at the base, and had barely missed crashing onto the ground (and my son) by hanging up at the last moment in another tree. It was immediately clear that he should not proceed with this aberrant endeavor, without help. My fate leaped before my eyes, and considering the hectic building schedule my construction business was committed to for that summer and fall, I grimaced at the thought. I had to force myself to acknowledge that a golden opportunity like this might present itself only once, every other lifetime, and besides, it is useless to attempt avoiding fate.

I ended up dedicating my annual sixteen-day summer vacation to the cause. I was an experienced enough builder to know that considering the shoestring budget and tight time frame, this feat was not going to be accomplished without lots of help. Fortunately, Freedle had many willing friends from all over the Valley.

The first several days involved cutting and gathering close to one-hundred, ten and twelve foot logs, including theone that almost whomped Freedle. The amount seemed ridiculous considering the small size of the structure. Old Blue, our woods truck, hauled most of these logs over an old logging road up to Falls Brook. From there they needed to be carried across the brook and up the steep bank, as the old logging bridge had been washed away years ago.

We quickly erected a rot-proof ten by twelve foot base, mostly from pressure treated scraps I had accumulated over the years, which rested on a few brook stones for a foundation. Then, finally, the main event could begin. The ends of each new layer of logs needed to be marked with a scribe around the underlying layer. Each log was then crosscut down to this semi-circular line and the waste chopped out with an ax so it would fit snuggly onto the log below.

For a builder accustomed to rapidly banging together large two-by lumber house frames, this was slow, tedious work. Fortunately I was propelled by a younger, fresher attitude, as for the most part, the kids seemed to find this laborious activity exciting. At times, watching their enthusiasm, I felt they were driven by some primordial urge handed down from their ancestors.

At the end of my summer vacation, the log work, including a loft deck, was finished. Looking at this simplistic box, an outsider would never believe how many people-hours were needed. As winter was rapidly approaching, we abandoned log construction, and assembled the gable ends (complete with a slightly curved base upon request) in my shop during any free time I could muster. On a few fall weekends we erected them along with the rafters and roof deck, which were the only material I had to buy. We thankfully managed to install used steel roofing and a plywood door before the snow came. A year later a donated wood stove was added making it a four-season shelter.

Now, aged by almost twenty years it still stands erectly, furnishing a resting point for sugarbush workers, and a peaceful shelter for sleepovers or anyone just passing by. After these many years I still find it gratifying to gaze upon its silhouette in the forest.

Lew Coty 2/24/13

Guilt Syrup

We made some especially nice maple syrup yesterday. It was early season light fancy which comes from the pan with bleached-bone white niter and is made only in cold, nearly freezing weather. I am finding the memory of its youthful, aggressive flavor hard to release. First run syrup often has an immature quality, but this was slightly later with a pubescent glow. Unlike its later, darker cousins, which are usually clothed in garments of caramel or coffee or chocolate, this syrup lay on the tongue with the raw, naked, seductive taste of pure maple essence. Strangely, I am feeling somewhat guilty of being a voyeur, having pierced the private, inner, secretly concealed aura of the uncultivated maple tree. Have I wantonly trespassed into this reserved-only-for-heaven realm? Sadly, this stellar flavor burns at both ends and its overwhelming allure will be noticeably diminished in a few months. We learn to indulge in this ephemeral delicacy while we can.

Lew Coty

March 9, 2008

Heat Stroke

On April 8th our sugar season officially ended. This may be a typical ending date, but typical would not be a fitting description for this sugar season.

We fired up the evaporator on February 23 which in our 33-year history is the earliest first boil. After a miserable, snow-stingy winter we were blessed with a three foot dump of snow on February 24th and 25th. The backcountry skiing was finally exciting again after a long drought. We finally had a respectable snow pack to help ensure a prolonged sugar season, or so we thought. Though the weather pattern in early March was less than ideal, we had made over 1500 gallons of mostly Fancy syrup by March 15, and I was enthused to be off to a good start. This enthusiasm was damped by an alarming weather forecast for the coming week, which called for record high temperatures every day. I know of nothing that will shut off a sugar season as quickly and completely as successive days in the seventies. It was tempting to shrug this off as computer-modeling with a loose wire.

Unfortunately, the computers were wired correctly. As the heat wave progressed, the sap flows diminished in intensity and the sap began to ferment creating obnoxious whiffs everywhere. The snow stake on Mt. Mansfield lost four feet of snow that week, and the woods became completely bare with only the denser man-made snow left on the ski trails. Falls Brook and its tributaries turned into twisted white ribbons of gushing water. Amazingly there was no flooding as the days were so sunny and dry. The Spring Beauties and leeks were sprouting everywhere – had I ever collected leeks in March? My mind drifted from syrup to gardening where the soil was warm and dry and the rhubarb leaves were emerging – had I ever gardened in March? I gazed in horror at fully developed buds on even our upper elevation trees. To make matters worse, there was a sinking feeling that in this era of global warming, we might have to become accustomed to this type of weather. I felt dazed as this tenacious heat was turning my bio-rhythm totally kittywampus. Sugar season had unquestionably sustained life-threatening blows.

Finally, there was relief including a hard freeze on March 27. The ensuing weather through early April was classic, near perfect sugaring weather. Sadly, the sap quality was not, as developed buds give the syrup an off-flavor. I don’t ever remember making so much beautifully light-colored, “buddy” Fancy syrup.

Sugar season continued to limp along in its traumatized condition. The arteries of its tubing system were being kept alive by a heart-lung machine called a vacuum pump. It was in agony on its final days and was painful to watch. On April 8th I mercifully turned off the pump. I believe sugar seasons, like people, deserve a death with dignity.

Lew Coty April 9, 2012

Nason

Did you ever know a Nason? I knew only one, and will probably never know another. The scarcity of Google results indicates it is not a mainstream name. This is confirmed as I write, by the squiggly red line under its letters trying to convince me I made a spelling mistake. It is easy to pronounce, rolling off the tongue without catching, and has a smooth, pleasant resonance. It seems to be left over from an older age, and has managed to elude becoming a trend without being totally reclusive.

It was the mid 70’s. I had heard from a hang-gliding friend who lived in Nebraska Valley that Nason Adams might be ready to sell some of his land there. I had entered my roaring twenties and had developed an uncontrollable passion for sugaring. My enthusiasm was well beyond sensible. With a college buddy, I had built a tarpaper sugar-shack on his parents’ housing lot. We had a few hundred buckets, most all of which were a quarter-mile away, on whose land I never knew. I was bursting at the seams, and the hillsides of Nebraska Valley looked like the perfect place to set up a real sugarhouse. I was young enough not to be bothered by the fact that I only had $680 to my name.

At the time, Nason owned most all of the land surrounding his house, on both sides of the road, in the central part of Nebraska Valley where it opens to its widest point. Sadly, times were changing and his way of making a living off the land was dying. The net income from selling maple syrup, cider and firewood was in a free fall while land taxes were rocketing. Nason had been making up the difference by selling land.

My friend and I approached him on a few occasions, and quickly discovered that Nason loved to chat and tell stories, but getting him to talk business was beyond our capacity. He indicated he might sell some land (maybe that knoll on the west side) but from there he quickly directed the conversation to more enlightening topics. I’m sure he was concerned we didn’t have the money, but his reluctance to talk price went beyond that. It seemed he considered attaching a price tag to part of his inheritance an indecent waste of time.

In desperation I asked a fellow who had recently purchased a lot from him, on the edge of what used to be his cow pasture, how he had managed to do it. He told me to take the time to get to know Nason and the ice would slowly melt. This advice worked, though it took over two years. At regular intervals we would visit and engage in long conversations, often about his recollections of life in Nebraska Valley. My youthful impatience was most always curbed by his peaceful manner and dry sense of humor, and I was frequently overwhelmed by his perfect recall of the past. Dipping into his wealth of memories, he might recall a day from forty years earlier, including the exact time of day, weather, and names of faces he hadn’t seen since, telling it like it was yesterday. He had an uncanny way of putting weird weather patterns or sugar seasons in perspective by comparing them in vivid detail to ones of long ago.

It was however his depth of sugaring knowledge that awed me the most. It didn’t matter that he hadn’t embraced the latest technology. His experience and innate sense of making maple syrup always both inspired and humbled me. Even after having sugared here for thirty-four years, whenever I was in Nason’s presence, up until the day he died, I was the apprentice.

Lew Coty December 12, 2013

Ozone Man

3/15/10

I fell asleep yesterday while leaning back on the kitchen chair. I had just eaten and felt momentarily on top of the frantic sugaring pace, when I instantly dozed off. Fortunately I awoke halfway to the floor and instinctively rolled sideways, barely avoiding a nasty head bang.

I call this depleted condition living in the ozone and sugarmakers are especially susceptible to it. When the trees decide to give sap, the world transforms into a state of immediacy. There is the physical endurance test of tapping and tubing maintenance in often deep, punchy snow, and the mental stress of dealing with mechanical problems that hammer at you in rapid-fire succession. Tubing systems and syrup making equipment do not come with instruction manuals and sugarmakers are left to rely on resourcefulness and improvisation. I am always amazed at how clever I can be when totally desperate.

Sap runs are relentless and non-retrievable. Waiting for tomorrow to deal with the situation after a good night’s rest is rarely an option. Bouncing between exigencies and sneaking in power naps are part of the game. Having your head bathed in hot steam for long periods completes the separation of mind from body. You focus on the immediate and float while you can over the rest.

Today, finally, the sap run has ebbed, and for the moment at least the crushing problems appear to have been dealt some knockout blows. I am falling out of the ozone with the usual hangover and renewed sense of peace and tolerance.

Rogue Check Valve

There are a few aspects of our sugaring operation, including our handful of bucket taps, and evaporator, that look much the same as they would have a hundred years ago. These are generally less prone to breakdowns and easily fixed. Then, there are the technological innovations, like our vacuum system and reverse osmosis (RO) machine that would have made a hundred year old sugarmaker stare in disbelief. Although these high-tech advances have made a dying, labor-and-fuel-intensive business profitable again, they do have a dark side. When even the most simple of a myriad of moving or electronic parts fail, the entire system is thrown out of whack.

March 1, 2013. The sap is just starting to trickle, and I’m in the sap shed turning on the vacuum pump. This pump is ten-horse power large and supplies vacuum to all of our ten thousand tubing taps. It connects to a release tank, which distributes the vacuum to all the mainlines through a port on top, and pumps the incoming sap to the storage tanks through a bottom port. When sap fills the release tank, a float trips the pump, which is powerful enough to pump the sap out against the vacuum. On the discharge side of the release pump is an inconspicuous one-way check valve that ensures the vacuum will not pull sap or air back into the release tank through the pump when it has cycled off.

After the initial release pumping this morning, a geyser erupts in the tank signifying the check valve is acting in a failed two-way manner. I give the valve a hammer rap, and this does the trick of reseating it. The second release is normal. Pleased with my canniness, I move on to more pressing chores, reminding myself to replace the check valve at a more convenient time, like when the sap lines are frozen. Returning fifteen minutes later, I see to my horror the valve has failed again, causing the overfilled release tank to spill its turbulence toward the mainlines and vacuum pump. The fix requires a double rap this time. To make matters worse, the sap run is picking up, generating a release about every four minutes. Soon, reseating the valve becomes more difficult, and I resort to jerking the discharge valves on and off, as well as increasing the number of raps. Desperately seeking a solution that doesn’t involve the formidable task of replacing the check valve, I even consider hiring a kid to babysit the pump.

I curse this repetitive nonsense for over an hour before finally facing the inevitable. Replacing the check valve means turning off the vacuum, which will surely kill this valuable sap run. I will also have to shut all the mainline valves so sap won’t inundate the sap shed when I take the discharge line apart. The check valve is in an awkward spot, requiring removal of multiple fittings. This will take time, and I worry that backing sap up hundreds of vertical feet might blow tubing fittings.

As fate has it, I only THINK I have a spare check valve. Rushing between hardware stores in town, I finally find a replacement, only to discover when I return that it’s the wrong size. After a few phone calls, I find the right size in a neighboring town. Just before I drive off to fetch it, I double check the size of the original purchase, and humbly discover it is the right size after all! Yes, I do apologize to the clerk whom I balled out for selling me the wrong size.

Somehow it doesn’t surprise me that the temperature plummets, and the sap run returns to a trickle soon after I finish replacing the check valve.

Scarlet Cup

Scarlet cups are the red flags of sugarbush cleanup. The brilliant crimson flashes are periodic attention grabbers that I find a good antidote to the drudgery of rinsing tubing. They are the earliest edible mushroom in our sugarbush often seen pushing up through the snow. They mostly seem to be shy, usually hiding as best they can in the brown leaf litter of the forest floor. With the exception of their flamboyant inner cup they are quite plain in shape and color. To make matters worse they lack the gift of a good flavor – the taste is rather bland. Some people are the victim of high expectations even though they have little to offer other than a god-given showiness. Such is the fate of the Scarlet Cup.

The Gift Run

There are happenings in life, amongst all the hard knocks, that generate renewal.

4/4/13: The sap run began slow, cloudy and late, with the stifled appearance of non-event. In the evening hours it found its calling.

4/5: It blossomed in the wee hours, largely unnoticed, and grossly underestimated.

Sugarmakers were forced to attention, and despite its rudeness, sang its praises.

This gift of nature had transformed a mediocre season overnight.

The gift, taxing the upper tanks.